OUT-LAW ANALYSIS 10 min. read

AI and copyright: a post-Data Bill UK timeline into 2026

Peter Kyle is responsible for tech policy within the UK government. Leon Neal/Getty Images.

20 Jun 2025, 1:04 pm

Pressure on the UK government to legislate on the issue of AI and copyright is expected to intensify in the months ahead as a statutory timeframe for action kicks into effect.

The finalised Data (Use and Access) Bill (DUAB) may not include the new AI-related copyright protections that the creative industry lobby and many parliamentarians were seeking, but it does provide stepping stones towards potential reform.

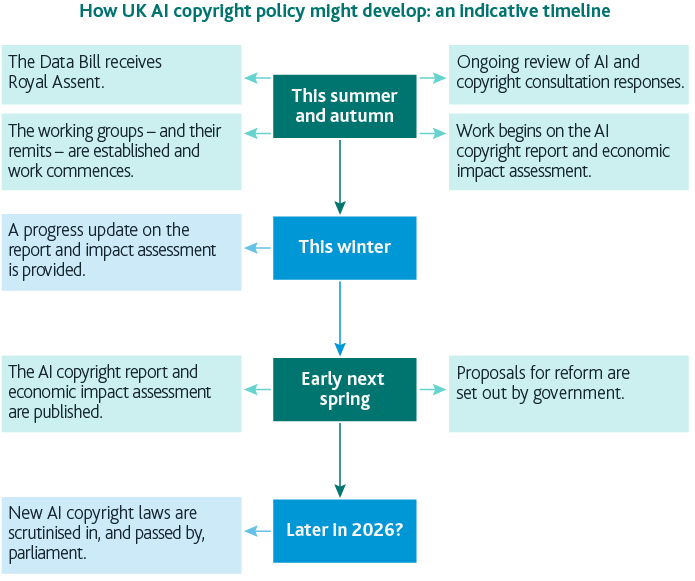

Below, we look at what AI developers and content creators can expect – and when – in relation to the UK AI and copyright agenda over the coming months:

A brief look backwards

Many content creators, such as publishers, authors and musicians, are concerned that AI developers are using their copyright works to train their AI models and inform the output those models produce. They want greater transparency over when AI developers seek to use their content as well as more control over whether to enable access to it – and, if so, to be remunerated in return. They argue that existing copyright protections in UK law are being ignored by AI developers and want the government to intervene.

AI developers, however, reject assertions that their activities are copyright infringing. They want the government to loosen, not tighten, restrictions on access to data and point to the potential of AI to deliver improved economic, social, health and environmental outcomes as the prize on offer for supporting AI development.

The UK government insists it is possible to balance the interests of AI developers with the creative industries. It opened a consultation on AI and copyright late last year, exploring options for legislative reform. At the time, it expressed preference for legislative change that would facilitate the training of AI models on the basis of copyrighted material – unless copyright owners ‘opt out’. That option would be underpinned with new transparency obligations for developers. The consultation closed in February and attracted more than 11,500 responses. The government has yet to formally respond to the feedback received.

The AI and copyright consultation period coincided with parliamentary scrutiny of the DUAB. The DUAB does contain some AI-related provisions but was not intended to be a vehicle for delivering copyright reform. However, amidst concerns over the government’s stated preference for reform, much of the parliamentary debate over the contents of DUAB focused on AI and copyright issues.

A split between law makers in the House of Commons and the House of Lords emerged, with peers repeatedly tabling amendments to DUAB aimed at enhancing copyright protections. This included amendments aimed at forcing the government to write new regulations to deliver greater transparency over use of copyright works by AI developers – and to do so within months. The amendments were resisted by MPs who backed the government’s conviction that the question of new AI-related copyright law should be considered holistically in a separate legislative process.

The parliamentary tug-of-war was the latest chapter in a long-running AI copyright debate in the UK: in 2023, the previous Conservative government rowed backed from plans to make copyright law more favourable for AI developers amidst pushback from the creative industries – and its subsequent attempt to foster agreement between the tech and creatives lobby on a voluntary AI copyright code failed when talks broke down last year.

What happens next?

While amendments that would have delivered substantive copyright reform for the AI age were not ultimately included within the DUAB, the Bill does compel the government to take actions to progress and inform the debate on AI and copyright reform in the UK. The government has also pledged to take further actions in the months ahead.

Economic impact assessment

The UK government has repeatedly asserted its belief that supporting AI development will be an enabler of economic growth. Some parliamentarians want to make sure that measures to support the AI industry that also impact the UK creative industries will deliver on that objective.

The government has nine months from the point the DUAB is passed to “prepare and publish an assessment of the economic impact” in the UK of at least the various options for copyright reform that it consulted on. The document, which is to be laid before parliament, must include assessment of the economic impact of each option on both copyright owners and those who develop or use AI systems.

Report on the use of copyright works in the development of AI systems

As well as an economic impact assessment, the government has nine months from the date DUAB is passed to prepare and publish a report on the use of copyright works in the development of AI systems (‘AI copyright report’) and to lay the report before parliament. Like the economic assessment, the report must consider the various options for copyright reform that the government consulted – and any other alternatives the government considers appropriate.

The contents of the report must include government proposals relating to various AI and copyright issues, including:

- technical measures and standards … that may be used to control the use of copyright works to develop AI systems, and the accessing of copyright works for that purpose;

- the effect of copyright on access to, and use of, data by developers of AI systems;

- the disclosure of information by developers of AI systems about their use of copyright works to develop AI systems, and how they access copyright works for that purpose;

- the granting of licences to developers of AI systems to do acts restricted by copyright;

- ways of enforcing requirements and restrictions relating to the use of copyright works to develop AI systems, and the accessing of copyright works for that purpose – including enforcement by a regulator.

The proposals must account for AI systems developed outside of the UK.

In drawing up the report, the government is required to consider the likely effect of the proposals, in the UK, on both copyright owners, and developers or users of AI systems. It must also have regard to the responses to its AI and copyright consultation.

Progress statement

The government is obliged to provide a progress report on the work towards publication of its AI copyright report and the economic impact assessment within six months of the DUAB being passed – if those papers have not been published by that point.

Working groups

The government is to establish two industry working groups to consider AI and copyright issues. One working group will explore the issue of transparency in relation to AI training, while the other will explore potential technical solutions that enable rights holders to control when their works are used by AI developers. The government said the working groups will feature representatives from both the creative industries and the tech sector.

A separate parliamentary group comprising MPs and peers is also to be set up to help develop UK AI copyright policy. Government ministers wrote to members of both Houses and the chairs of four existing parliamentary committees to advise them of the intention to establish this working group and to invite interest in participating.

The precise make-up and remits of the working groups have yet to be confirmed by the government. However, some insight into their role in the months ahead can be gleaned from statements made by government ministers.

Baroness Jones, parliamentary under-secretary of state for the future digital economy, told peers that, together with the responses to the government’s AI and copyright consultation, the work of the working groups will “inform the reports, the proposal and the economic assessment” that the government must prepare under the DUAB. She said that it is possible that the working groups “bring other benefits”, alluding to the possibility of “interim voluntary arrangements” being put in place “until longer-term solutions can be agreed upon and implemented”.

Sir Chris Bryant, creative industries minister, said he hopes the industry working groups can deliver effective, simple and accessible “technical solutions”. Examples in that regard could, he said, include greater transparency about AI training or standards on web crawlers, metadata and watermarking.

Bryant said: “If we could get to a technical solution to rights reservations, so that AI companies have the security of knowing what material they are using – that they are scraping or ingesting – and creative industries know that their work is being used and can either say, ‘No, you can’t use it,’ or, ‘If you are going to use it, you are going to remunerate me,’ whether that is individually or as part of a collecting society, that would be a significant advance for us.”

Factors that will shape the contents of any new UK AI copyright law

Government ministers have been keen to emphasise that the AI copyright consultation process – and the operation of the various working groups, as well as preparatory works on the DUAB AI copyright report and economic impact assessment – must be allowed to run its course before any firm decisions are taken in relation to UK AI-related copyright reform.

Legislative intervention is also not guaranteed. Bryant has told MPs that no new AI copyright laws will be brought forward by the government and that reform will not be implemented “unless and until we are confident that we have a practical, practicable and effective plan that meets our objectives of enhancing rights holder control, providing legal certainty around AI firms’ access to content, and providing transparency for rights holders and AI developers of all sizes”, adding that the government “will not move forward with such a package unless there is a technical solution to the question of how people can reserve their rights”.

There are clues on what any new UK AI copyright law could contain if and once those hurdles are overcome, however.

Bryant, for example, has signalled that clauses providing “effective and proportionate” transparency over the use of copyright works in AI training, will form part of any new framework. However, some UK law makers fear that delay in the implementation of this new transparency regime will make it more difficult for rights holders to identify use of their works in AI training in future.

Other provisions on enforcement and remuneration are also expected to feature.

On enforcement, Bryant has ruled out a role for the government in enforcing copyright law, telling MPs instead that the law as it stands “makes it very clear that infringement is actionable by copyright owners” or by prosecuting authorities and that the government “are not changing them in a single regard”. Bryant had previously pushed back on proposals drafted by peers which envisaged a role for the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) on enforcement of any new transparency obligations.

On remuneration, Bryant has said both he and Peter Kyle, the UK technology secretary, want to “get to a place where there is more licensing of copyrighted material by AI companies”. He added: “I do not think anybody expects that the labour of others should be handed over to third parties without recompense or control.” Bryant said finding a practical solution in that regard for individuals that are not necessarily part of a collecting society is one of the “issues that needs to be addressed”.

The Copyright Licensing Agency (CLA) is in the process of developing a new gen-AI training licence that it says will “provide a scalable collective licensing solution that ensures remuneration for publishers and authors – in particular those not in a position to negotiate direct licensing deals – and give AI developers of all sizes the legal certainty needed to use a broad range of content to innovate and train language models”. The new licence is expected to be available for use in the third quarter of this year, according to the CLA.

Baroness Jones said: “Our plan will give copyright holders as much protection and support as possible, including via transparency, enforcement and renumeration, while not pre-empting the outcomes of the important and necessary processes that we have set out and without pre-judging any future legislation. We want to ensure that we uphold our gold standard copyright regime while also adapting to the new challenges.”

The contents of any new UK AI copyright law could also be influenced by external factors. For example, the dispute between Getty Images and Stability AI currently being considered by the High Court in London might determine how UK copyright law applies in an AI context currently, but it is possible that the ruling could shape how the law is reformed for the future. The court’s ruling is expected later this year. UK AI copyright policy is also likely to be influenced by political, legal, technical and commercial developments, globally, as we explored in more detail recently.

Timeline uncertainties

The timeframe for some expected developments is unclear. Those developments include:

- When businesses can expect the government to publish a summary of the responses it received to its AI and copyright consultation – it seems possible, at least, that this will only happen when the DUAB AI copyright report and economic impact assessment are published;

- When the industry and parliamentary working groups will complete their work;

- When the government will bring forward legislation – there is a question over whether proposals the government brings forward as part of its report will be in the form of a draft Bill. Bryant told MPs in March: “There should be a proper primary legislation process, which may not happen for another 12 to 18 months, or even two years. I do not know.”

Two waves of reform?

There are suggestions that reform could come in two distinct waves.

Baroness Jones told peers earlier this month that the government is “looking at the case for more comprehensive AI legislation that delivers on our manifesto commitment [of growing the creative industries as part of its broader industrial strategy and growth agenda]”. She said she expects “any comprehensive legislation to address the opportunities and challenges presented by AI to the creative sector”.